The Teardown

Wednesday:: January 31st, 2024

👋 Hi, this is Chris with another issue of The Teardown. In every issue, I cover how daily life evolves in concert with the technology we use every day. If you’d like to get emails like this in your inbox every week, hit the subscribe button below.

Intro: What Pitchfork Was

I’m late to this news: you might have heard that Condé Nast decided to fold music review site Pitchfork into GQ. Media reporter Max Tani shared a brief internal Condé Nast memo about the move. I am highlighting just the opening paragraph of the memo:

Today we are evolving our Pitchfork team structure by bringing the team into the GQ organization. This decision was made after a careful evaluation of Pitchfork’s performance and what we believe is the best path forward for the brand so that our coverage of music can continue to thrive within the company

Translation: Pitchfork doesn’t generate enough money. We need to evolve into a more efficient operation. Pitchfork will still be a website. For how long? Place your bets. Long live our GQ overlords!

Pitchfork was famous for its music reviews, provocative snobbery, and disdain for anything that didn’t fit the subjective mold of its writers and editors. The site blossomed careers for many artists and wiped the floors with others. A Variety article from 2019 illustrates the latter dynamic:

Former Pitchfork critic Matt LeMay offered a mea culpa on Friday, apologizing to Grammy nominated singer Liz Phair for a review he wrote of her 2003 self-titled album. The famously scathing take-down gave the album a score of 0.0 on Pitchfork‘s scale of 8.0.

In an in-depth Q&A with Vulture published on Sept. 5, Phair, who is releasing a book, “Horror Stories: A Memoir,” said that she was proud of receiving a 0.0. But in reading back what he wrote, LeMay did not feel the same.

In a lengthy multi-Tweet thread, LeMay pointed to his age — 19 at the time — as the main culprit in writing “the condescending and cringey” review.

In the original critique, which took issue with Phair’s collaborations with established pop writers, LeMay wrote that the album “could have just as easily been made by anybody else” and described the songs as “gratuitous and overdetermined, eschewing the stark and accusatory insights of ‘Exile in Guyville’ in favor of pointless F-bombs, manipulative ballads, and foul-mouthed shmeminism.”

The words condescending and cringey don’t apply to just one article from Pitchfork. The site was almost immaculately designed to be pretentious. It was almost as if Triumph-The-Insult-Comic-Dog attended an Ivy-league school to achieve a Master degree in writing and fully-charged vocabulary.

Pitchfork first arrived on the internet scene in 1996. I was 14. I didn’t discover the site until several years later during sophomore year in college. By then, Pitchfork was well along in developing its aforementioned reputation.

But, crucially, music discovery was a manual process. FM radio was a juggernaut. Morning and prime-time on-air jockeys possessed real power over what was exposed to the public, or stashed away. And, you could read Rolling Stone or other similar publications to learn about new music and other adjacent topics.

If taken today, both paths require some level of work and attention:

Radio is passive but requires knowledge of stations and their intended genres. You may also listen for a long time before hearing something new you really like.

Reading is active and requires focus. It’s hard to skim and subsequently digest a written review. You need to focus on the story. Also, you might want to listen to the song or album while reading the review. Doing so complicates the brain’s ability to focus.

Pitchfork didn’t change this latter model in a substantial way. It was (is, for now) available for free on the internet, supported by advertising just like vast numbers of other businesses. In that sense, it was similar to tower-broadcast radio - supported by ads, not by subscriptions. Rolling Stone, by contrast, supported itself with both. Ads of all shapes and sizes throughout its pages, and an off-the-shelf or delivery-subscription price.

Technology Steps Up To The Plate

Starting in the late 90s and continuing into the 2000s, consumption choice exploded. Discovery through the traditional sources existed, yes, but so did discovery through internet-native platforms. One famous platform was Napster. It wasn’t a pure discovery platform so much as a gigantic bucket full of anything you might want. So, finding something new in general or new to you required the motivation to search. It was all there, legal or otherwise.

I attended college from 2001-2005 and recall a similar campus-specific site. It was our Napster-like intranet. Today, almost 20 years later, I have loads of songs sitting on back-up and cloud-share drives from hours of browsing and downloading

Another fledging media form took shape at the time: blogs. Hosting platforms like Blogger.com and Tumblr allowed anyone to publish anything. With that freedom, regular music fans and more enamored aficionados created blogs dedicated to music. One might be about hip-hop, one about pop, and another about deep house. Sometimes their respective writers simply spewed words into the internet ether, but some caught fire and became popular destinations for discovery.

These blogs weren’t obvious competitors to sites like Pitchfork at first. They didn’t experience and momentum of Pitchfork. But they did have the marginal distribution advantage: one post could effectively replicate millions of times over. The blogger in his or her cramped editing room needed only to publish something and link or embed a song.

Pitchfork also benefited from internet distribution but with one major disadvantage: the structure and overhead of an actual media organization. It had to sustain it’s costs over time. It needed to make to make a real profit to be a real business.

Semi-Automated Discovery

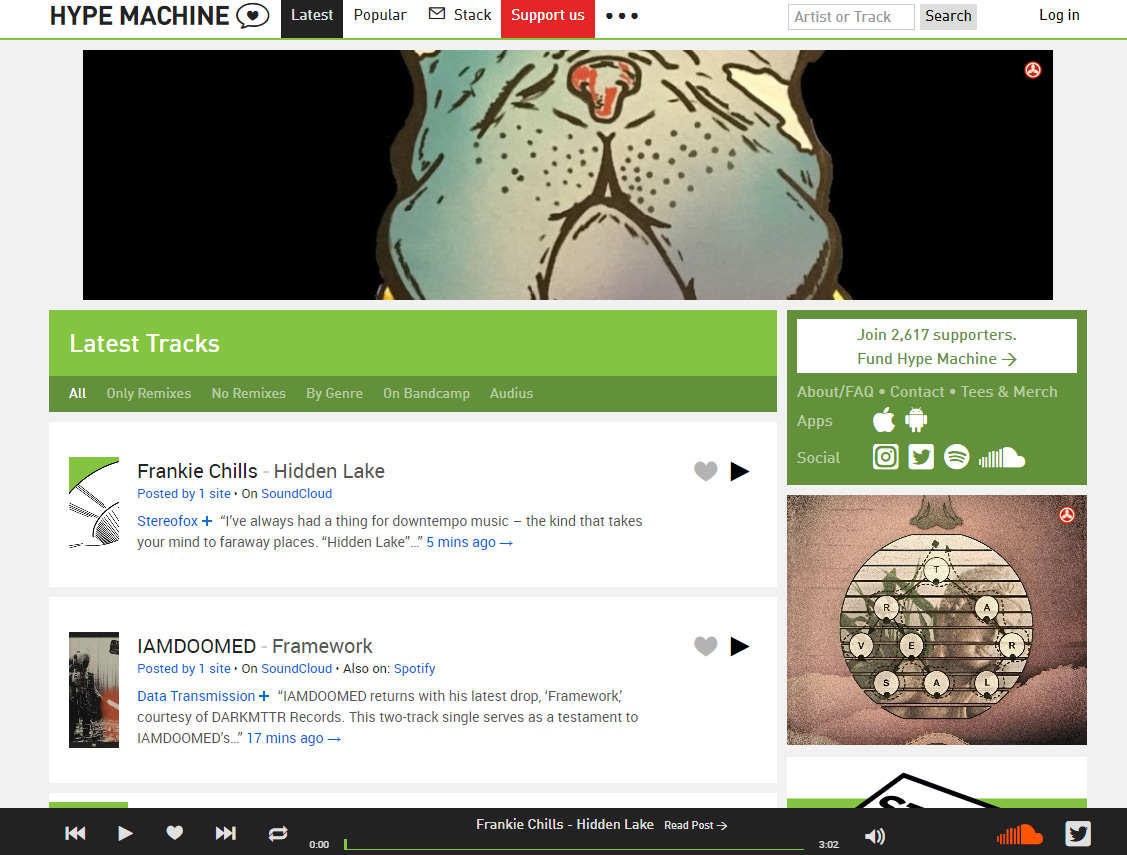

That conundrum didn’t stop the blogs. Instead, an ecosystem sprung up around them. In 2005, a young programmer named Anthony Volodkin created a website called The Hype Machine (colloquially: Hypem). It’s still alive and kicking today, and doing what it did well from the early days. Hypem aggregates music content from many blogs and provides consumers with of the latest trends across those blogs. A 2007 article in Wired highlighted the genesis of the idea:

TAKEN ON THE whole, MP3 blogs offer more breadth, depth and music than a magazine or radio station ever could. But how, exactly, does one take MP3 blogs "on the whole"? That's the question answered by MP3 blog-indexing sites like the Hype Machine -- the creation of the now-21-year-old Anthony Volodkin.

In 2005, Volodkin found himself frustrated by music magazines and radio stations, which seemed stale, slow and suspect. He had become fascinated by MP3 blogs, which since 2003 were posting actual MP3s of the music they reviewed, rather than just talking about how the band dressed and who they claimed as influences. After spending too many nights scouring MP3 blogs for new music, he decided to automate the process. The result is Hype Machine: A live index and music-streaming station consisting of whatever's being talked about on MP3 blogs.

I used the phrase “semi-automated” because the site relies on both software and human touch to provide the end-user experience. In one corner is Hype Machine’s software, built to index and ingest music content from over four-hundred music sites. In the other is Hype Machine’s team, quite literally limiting the index by requiring users to submit their ideas for future indexing. The team won’t add everything. There are other guardrails too.

The Wired writer added a blurb that signaled an ominous future for music discovery as a whole.

Wired News: There's a David Byrne quote you may have seen: "Soon enough a site will open that is like a Google search for music downloads -- downloads that are not copy-protected but you still pay for … a meta-search will turn up the tracks you want, wherever they live, on whomever's site. Consumers don't care who they buy them from if the interface is easy and intuitive." It strikes me as similar to what you're doing on Hype Machine with blog indexing. Do you see yourself also setting up a similar service that scrapes all the stores, such as Other Music's?

Let me highlight one specific line in that quote: consumers don't care who they buy from if the interface is easy and intuitive.

Should I think of some variations? Let’s try:

Consumers gravitate to easy, low-friction, convenient experiences

Consumers don’t care where suggestions originate. They want them convenient, packaged, and succinct.

Hypem solved some of these problems. You didn’t navigate to individual blogs. You didn’t download files. You didn’t sign into elicit file-sharing sites or torrents with questionable legal status. You didn’t need to construct a playlist to start listening. You went to the site and hit play. There wasn’t much friction at all.

So, while Hypem was a better experience than visiting fifty blogs for new music, it didn’t have it all. It wasn’t one all-encompassing addict-like experience. The site focused on exposing music, letting you play, and then handing off your experience to some other tool or home-grown solution

Pitchfork was, largely, still Pitchfork despite other business ventures: a place for music critique that didn’t resonate with an extremely scalable audience. Articles took time to read. Pretentious articles took even longer, perhaps leading to full-blown context switches. Time has always been a precious resource

The Robots Appear

What lurked in the background, eerily foreshadowing the quote, was a model like Spotify. Note that I am describing the concept broadly because Spotify was and is hardly alone in music. But it is an overwhelming competitor in the space. I’m using it as an example forward from here.

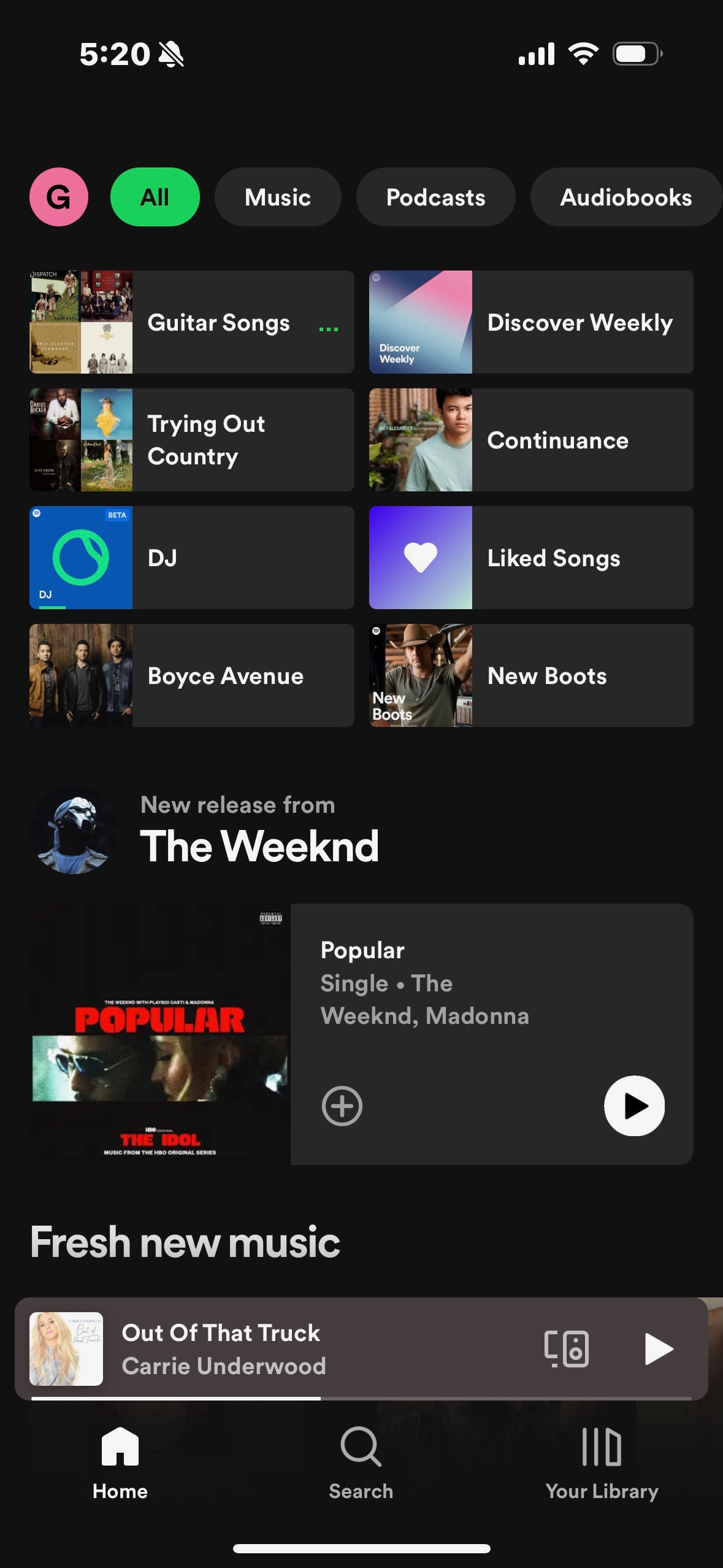

Spotify initially provided something that wasn’t obvious elsewhere: a one-stop consumption experience for an ever-changing internet-connected consumer. Old habits were on the way out. It had easy search, browse, and playback entirely within one interface. The platform also leveraged the explosion of mobile device usage.

And, key to this story: it had access to the back catalogs of artists on the platform. There were public and private disputes over that access, but the vast majority of artists decided to be where fans were rather than challenge those groupies to discover and listen through esoteric means.

It’s also worth highlighting the engineering prowess of a company Spotify at the time. It was a bonified start-up. Talented engineers happily accepted cash and equity to build the future of music consumption.

Over time, those engineers and their product managers created features that wiped out the need for many other discovery methods: mixes.

Today, when you open the app, you have access to various algorithm-driven playlists that contain both songs you listen to and stuff you haven’t yet heard on Spotify. An example is Spotify’s new DJ feature. From Spotify’s website:

Ready for a brand-new way to listen on Spotify and connect even more deeply with the artists you love? The DJ is a personalized AI guide that knows you and your music taste so well that it can choose what to play for you. This feature, first rolling out in beta, will deliver a curated lineup of music alongside commentary around the tracks and artists we think you’ll like in a stunningly realistic voice.

It will sort through the latest music and look back at some of your old favorites—maybe even resurfacing that song you haven’t listened to for years. It will then review what you might enjoy and deliver a stream of songs picked just for you. And what’s more, it constantly refreshes the lineup based on your feedback.

I won’t go into the DJ feature in detail - that’s not the point of this post. The notable bits are these:

AI drives the DJ feature. Does it require iteration, tuning, and development in the background? Yes, from those same engineers. But it is distributed and used instantly by hundreds of millions of people. DJ has the advantage of and access to rare consumer scale

It’s available in the same app and interface as everything else Spotify offers.

It’s the last of these two points that sticks with me. I use DJ from time-to-time, harking back to a time when I listened to Boston’s WBCN and WAAF rock stations at home and in my car. I relied on DJs from those stations to expose new songs and play my favorites. But further discovery and acquisition was up to me. I had to remember the songs, then find the albums, buy them from physical stores, and maybe rip them to my computer for pure offline electronic listening. Like many of you, I was proud about this collection, much as Harvey relishes his record collection in the show Suits.

User Experience Wins This Battle

With Spotify and DJ, the entire consumption experience happens within a single app accessible wherever I am, whenever I want it. Most of us don’t need Pulitzer-quality music journalism to find new songs. I don’t need to remember anything because I can add a song to a playlist with one mash of the screen. And, on the off-chance I’m out and hear something over a loudspeaker, I’ll capture the song with Shazam and add it to Spotify. Spotify knows everything from that point forward.

Say what you want about Spotify’s interface, but it gives me everything I want on one screen, right now. Yes, those are country playlists and albums in the image. You stop it!

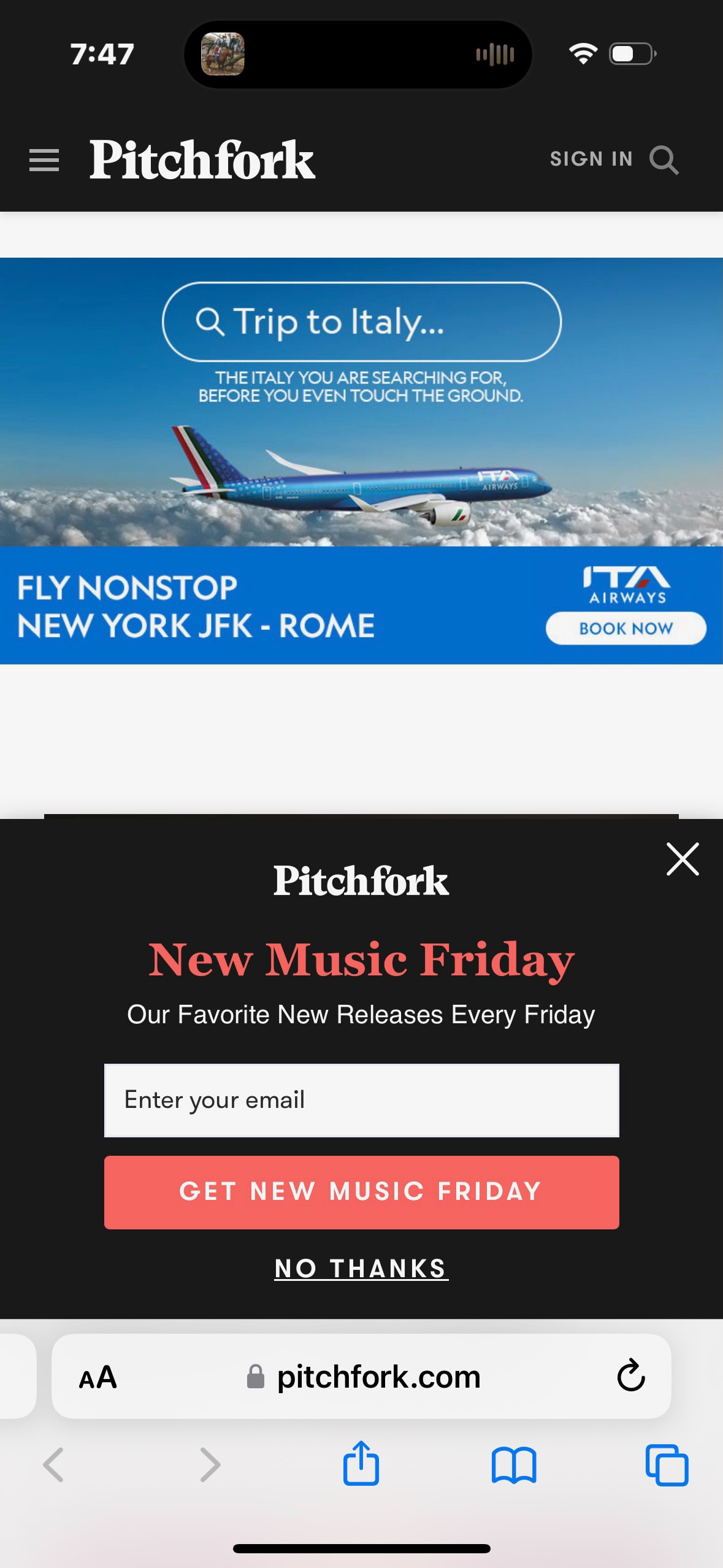

In contrast, what’s left of Pitchfork doesn’t stand much of a chance. I’m presented with the screen below after one quick thumb scroll in my phone’s Safari browser:

There’s an ad. There’s a request for my email with an unclear value proposition. I haven’t clicked on any reviews and otherwise barely scrolled the site. Safari tells it’s blocking all kinds of ad trackers.

Say what you will about external forces and their impact here: the internet, streaming, ads, and unstable business models all played a part. But, the experience is what matters. Pitchfork is no longer it.

lol those screengrabs at the end. Love it. I also think about how I make my playlists for holidays and home entertaining by hand, but it’s a serious time commitment (and one I don’t think most people want to undertake).

Since I worked at the mall in high school, I remember going to the music stores and listening to albums set up on the music stations. Although not sure if I discovered anything cool or not that way. I do sort of miss downloading random peoples music libraries on Napster or limewire, but the first few years of Spotify were a music discovery dream. I still listen to a lot of the random music I found back in 2011/2012.